Spinal Fusion Surgery – Consultations and Informed Consent

Setting the Scene

In this case, the patient had been suffering from mild lower back pain radiating down the back of the legs for many years. After time the pain escalated, and they were referred to a spinal surgeon by their GP.

At the consultation, the patient consented to undergo spinal fusion surgery which occurred approximately 6 months later. Unfortunately, the patient had a poor post-operative recovery and complained of severe headaches, nausea, photophobia and exacerbated back pain. Two years later, the patient consulted another spinal surgeon who queried whether this surgery had been the only option at the time of the previous consultation.

Main Learning Points

-

To prove or disprove the allegations made, the details of the documentation become crucial, especially some years after the incident. In this case, the patient interpreted the advice given orally in a distinctly different way from the surgeon. Without sufficient or legible detail in the written notes (clinical letter and consent form), it is difficult to prove what was discussed.

- Following the consultation, the clinic letter sent to patients gives ample opportunity to clarify recommendations for treatment and to highlight potential drawbacks or side effects of post-operative rehabilitation. It should accurately reflect what was discussed orally so there is no misunderstanding at a later date. Statements should be clear and comprehensible as those which are vague in tone, such as ‘relief of symptoms’, can leave clinicians vulnerable to litigation.

Reducing the Risk of Litigation

In light of the Montgomery case, by not keeping detailed, legibly written documentation clearly indicating what had been said at the consultation, the surgeon put themself at increased risk of litigation, and was in a difficult situation to prove otherwise. TMLEP highlights the following:

-

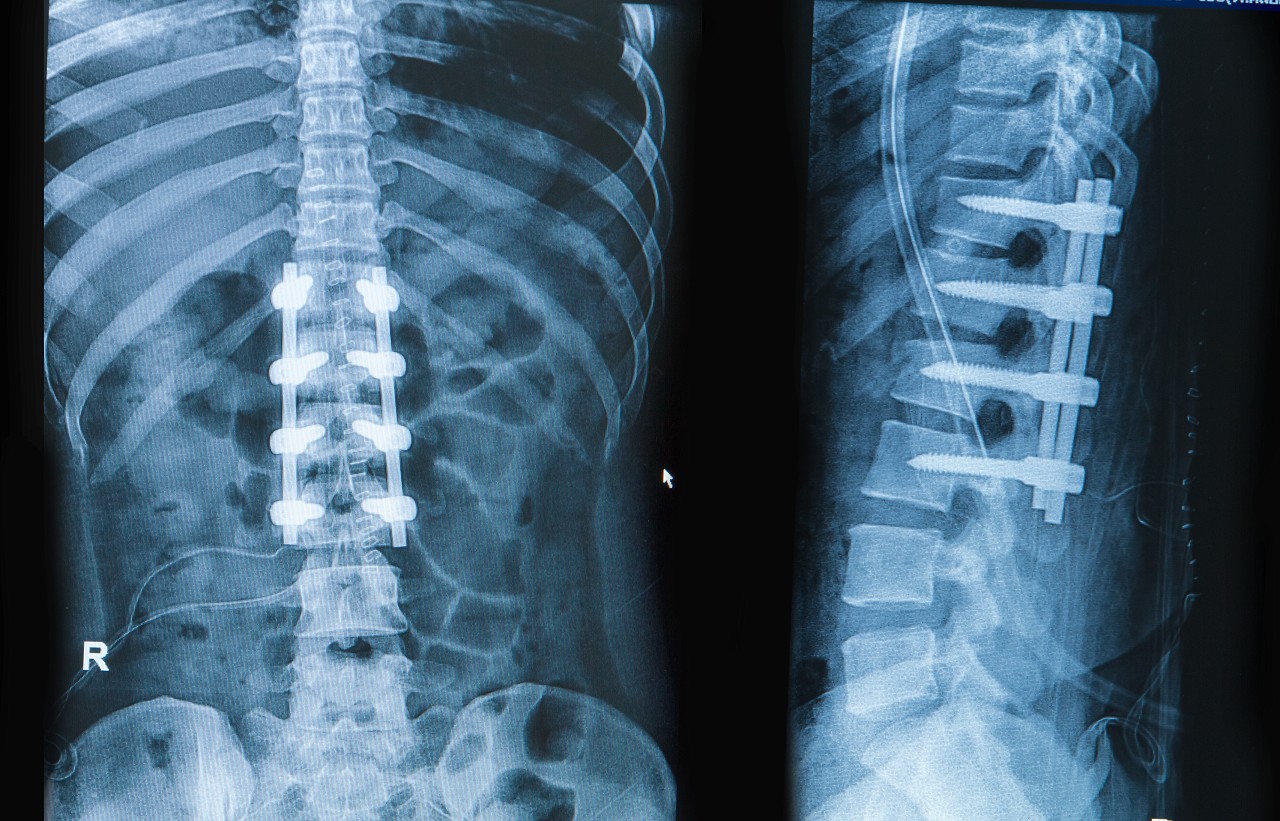

That written documentation in the Clinic Letter and/or Claim Form accurately reflects the oral discussion that takes place at the consultation. This should be clear and legible, even if handwritten. It should also be documented that a patient’s medical records and any scans or x-rays have been viewed and considered in the approach the surgeon takes.

-

That the percentage risks of side effects or poor outcome is clearly understood by the patient prior to giving consent. In this case, it was documented that the patient suffered from fibromyalgia, fatigue and mood swings. (Fibromyalgia is a disorder characterised by widespread musculoskeletal pain accompanied by fatigue, sleep, memory and mood issues. Researchers believe that fibromyalgia amplifies painful sensations by affecting the way your brain processes pain signals.) Surgery is not considered the optimum method as a solution for fibromyalgia, as there is a high risk of poor surgical outcome, however, this was not discussed with the patient and the risks of worsening pain and other potential problems post-operatively were not fully explained to the patient before they signed consent.

-

Alternative solutions, if available, are understood by the patient. In this case, at the initial consultation the patient should have been informed of any alternative to spinal fusion surgery, such as steroid injections in conjunction with physiotherapy to alleviate the crippling back pain.

- Patients should be provided with additional information about the intended procedure including printed documentation and other online resources. For example, when listing someone for surgery, it is recommended they are given an information booklet as well as the corresponding information from the British Association of Spinal Surgeons (BASS). Additionally, all patients should be seen in a consent clinic 2-3 weeks prior to their surgery in order to answer any further questions they may have and complete the required consent forms.

In summary:

In order to reduce the risk of litigation at a later date, it is imperative that informed consent means exactly that. A patient needs to be informed of the pros and cons of undertaking surgery, any alternative procedures possible and the percentage risks of poor post-operative outcome in order to make a proper informed decision. The more complicated the surgery, the more detailed the explanation needs to be.

Clinicians need to be aware that if they do not have clear, accurate written documentation, sighted by the patient, they can be open to litigation, as it becomes a battle of interpretation. In this case, the patient had alleged that the surgeon had said that spinal fusion surgery was urgent and the only recourse available. However, the surgery did not take place for 6 months and it was only this fact that cast some doubt on the claimant’s version. Urgent surgery would have been planned much sooner. This time lapse also gave the patient ample time to reconsider their options and does not substantiate the allegation that the surgeon had hurried them to make a decision.

Some of the written evidence in this case was handwritten (Consent Form) and was illegible in parts which weakened the surgeon’s position in this case.